Lets talk Enumeration - Part 1

Posted on September 10, 2019 • 7 minutes • 1438 words

Enumeration is one of, if not the most, important part of any CTF. Since this is one of the most key parts of doing CTF’s and Red Team Engagements, I feel it deserves some focus. I often see quite a few people asking for help on CTF boxes only to be told to enumerate more because they didn’t do enough or are unfamiliar with how to do ‘more’. This series of articles will focus on making Enumeration easier for those that might not know how to go about doing it.

The first few parts of this series will focus on 3 -4 external enumeration tools. The following post will focus on internal enumeration tools and techniques.

The tools we are going to cover in this post are Nmap, Dirb, SMB tools and Wfuzz.

We should note that the commands listed are simply the basic entry level commands. There are much more extensive and maybe more practical tools and commands to be run. I urge you to research those as you become more comfortable with the basics listed here.

Nmap

Nmap is the go to tool for network enumeration for most. A very powerful tool for enumeration. It has the ability to discovery, fingerprint, test and even escalate priveldges! You can read more indepth about Nmap here .

Lets go over some common nmap commands. Each command will be given with a breakdown of what the command flags are.

Example 1: This is my go to standard scan command.

nmap -sC -sV -oA ./ScanName 10.0.0.2

The -sC tells nmap to use Default Scripts.

The -sV tells nmap to enumerate Service Version.

The -oA tells nmap to output the scan results into .xml, .nmap and .gnmap formats called ScanName.

Example 2: Scan all ports on a box.

nmap -p- -oA ./ScanName 10.0.0.2

The -p- tells nmap to scan all ports. An out of the box nmap scan will only scan the top 1000 ports. Often in many CTF’s things are running on obscure ports, this will help find them.

The -oA tells nmap to output the results to three files called ScanName.

Example 3: Scan a box on specific ports or ranges.

nmap -T5 -p 80,443 10.0.0.2

The -T5 dictates the speed of the scan. 5 being the fastest (and sometimes least accurate). While 0 being the slowest and most accurate. The default speed that nmap scans at is 3.

The -p 80,443 will scan those ports only.

Example 4: Scan a box even though we know its online.

namp -sC -sV -Pn -oA ./ScanName 10.0.0.2

The -Pn tells nmap to treat the host as its is online. Often times results can be hidden or filtered out causing nmap to read as an offline host.

The -sC tells nmap to use Default Scripts.

The -sV tells nmap to enumerate Service Version.

The -oA tells nmap to output the scan results into .xml, .nmap and .gnmap formats called ScanName.

Dirb

Next on the list of enumeration tools is dirb or dirbuster (the GUI counterpart). Gobuster has been a tool that has replaced this for many due to it’s speed. Functionality is largly the same. Dirbuster is used to enumerate directories and files on a website based on a wordlist. Enumerating a web directories and files is used in just about every CTF.

If you are unfamiliar with using word lists for tools, you should take a quick look at the following path on your Kali / Parrot OS. /usr/share/wordlists/. Here you will find a list for everything you might need. This directory is broken down into subdirectories that contain even more lists. You get the idea right?

So now that we know where all of our passwords and lists are. Lets look at some examples of how we can use dirb to enumerate http services.

Example 1: A basic scan.

dirb http://10.0.0.2/ -o ./machine_scan.txt

This will be a quick and dirty scan. You’ll notice that dirb doesn’t require you to supply a wordlist. This is because it will use a default common wordlist (located here: /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt) if you do not specify a list.

The -o tells dirb to output the results to the file machine_scan.txt in our current working directory.

Example 2: A scan with no recurssion.

dirb http://10.0.0.2/ -r

The -r tells dirb to skip recurssion. By default dirb will take a fist pass with the word list. After it has completed, it will go back to the directories it has found and repeat the process. So if you have a fairly large directory structure, dirb could spend too much time scanning.

Example 3: A scan with a custom word list

dirb http://10.0.0.2/ /usr/share/wordlists/dirb/big.txt

This example, we simply supply the path to the wordlist we want to use after we select our target.

Example 4: Scanning for specific extensions.

dirb http://10.0.0.2 -X .php

The -X will tell dirb to take that word list and append a .php file to each of them. So if our list is cat, dog, mouse. dirb will test the website for cat.php, dog.php and mouse.php. This is how we scan for specific file extensions. You can also specify multiple extension by separating them with a comma. dirb http://10.0.0.2 -X .php,.html.

SMB Enumeration

There are quite a few SMB enumeration tools. When doing CTF’s I tend to only use SMBMap and SMBClient.

You initial enumeration from Nmap should have shown you if port 139 and 445 are open. These are the standard SMB ports. You can use the following to further enumerate those services.

Example 1: Enumerating shares with smbmap.

smbmap -H 10.0.0.2

The -H specifies the target host. If SMB 1 or 2 are enable, generally you can enumerate the shares with this command.

Example 2: Enumerating shares with smbclient.

smbclient -L \\\\10.0.0.2

The -L tells smbclient to list all shares.

The \\\\ is a bit odd if this is the first time you are seeing it. We are escaping with the first \ and letting Linux register the following one. So we essentially have 4 slashes to register 2.

After running this command you can often be prompted for credentials. You can hit enter to bypass that or we can do something like echo exit | smbclient -L \\\\10.0.0.2. This will avoid having to enter a password prompt.

Example 3: Enumerating shares with credentials.

smbmap -u 'turtle' -p 'ninja' -d 'htb.local' -H 10.0.0.2

The -u specifies a user, in this case turtle.

The -p specifies the above users password, ninja.

The -d specifies the workgroup for the machine, if applicable.

Example 4: Connecting to a share.

smbclient \\\\10.0.0.2\\Backup -U turtle

Similar to above, the -U specifies the username, turtle.

Smbclient will then prompt you for the password. Alternatly you can enter the password at the end of the username with a %, like this: smbclient \\\\10.0.0.2\\Backup -U turtle%ninja

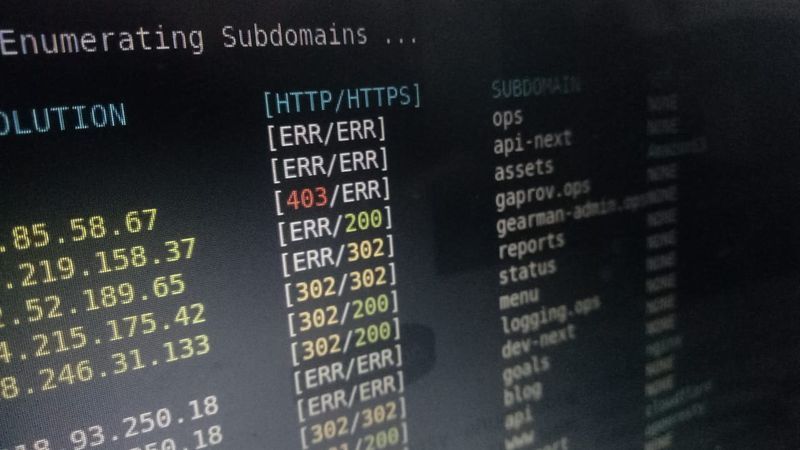

Wfuzz

The final tool I wanted to breifly cover is wfuzz. This can be considered more of a bruteforce tool but it can also be used to do enumeration as well. You can feed wfuzz a specific part of a URL and it will use a supplied wordlist to determine if it exists.

Wfuzz will use the word FUZZ as its identifier in the command. It then places the item you want in that place. Commonly a word or some kind of payload.

Example 1: Fuzzing a file name.

wfuzz -c -w /usr/share/wordlists/villians.txt http://10.0.0.2/FUZZ.php

The -w tells wfuzz to use a wordlist. It will then take each entry in the file villians.txt and place it in the FUZZ spot of the URL.

Example 2: A basic fuzz for numbers.

wfuzz -c -w /usr/share/wordlists/numbers.txt -hc 404 http://10.0.0.2/php?pageID=FUZZ

The -c just makes it colored and I like colors.

The -hc will the responses of 404.

Example 3: Fuzzing a POST request.

wfuzz -c -w /usr/share/wordlists/username.txt -d "username=FUZZ&pass=FUZZ" --hc 302 http://10.0.0.2/login.php

This command is a bit more complex looking. What we are doing is trying to enumerate a username and password that are the same. Maybe root:root or admin:admin.

The -d to tell wfuzz we want to fuzz form-encoded data.

We hide the 302 response with -hc.

Now if you knew a username you can use this same teqchnique to brute the password by replacing the first FUZZ with the username. It would look like this:

wfuzz -c -w /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt -d "username=admin&pass=FUZZ" --hc 302 http://10.0.0.2/login.php.

Wfuzz has much more use cases, like fuzzing cookies, headers and authentication types to name a few. I will eventually circle back around to this tool when we get to some more complex tools.

Hopefully this helps those that aren’t familiar with enumeration, get an idea of some starting points and application use cases.